Supply Chain: Issues & Analysis: Restrictions and Exclusivity

1. Overview

Competition law is a significant issue for all operators in a supply chain.

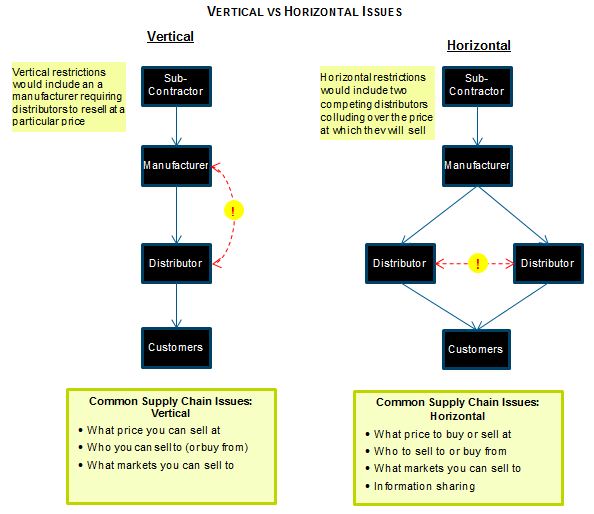

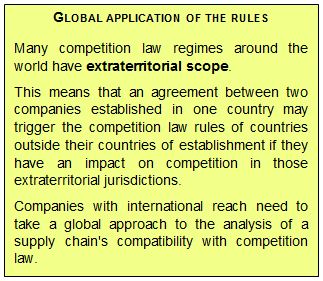

There are two distinct categories of potential issue arising competition: vertical activity (i.e. aspects of the relationships between suppliers and customers which have an anti-competitive effect) and horizontal activities (i.e. anti-competitive behaviour between competitors such as collusion between customers or suppliers).

"Vertical" agreements between companies at different levels of the supply chain (e.g. between buyers and suppliers, or between manufacturers and intermediate distributors) are generally less susceptible to competition law concerns than horizontal agreements.

However, there are still areas of potential risk.

Competition law issues can arise in the "upstream" supply chain (eg with how goods/services are sourced) and also in the "downstream" supply chain (eg with how goods/services are sold).

Upstream, there can be issues under certain circumstances where there is market power combined with exclusive supply, joint purchasing arrangements and most-favoured-nation clauses (which mean that suppliers cannot charge other customers a lower price).

Downstream, agreements that relate to minimum resale prices, that set prices at levels below the seller's cost, or that discriminate among similarly-situated buyers can all infringe competition law under certain circumstances.

It is important to look carefully at supply arrangements, and verify that there are not in place arrangements which raise in effect "hidden" competition law issues. Illegal retail price maintenance may occur, for example, not as a result of having a specific clause relating to resale prices, but as a result of suppliers placing pressure on retailers to deter discounting with threatened or actual delisting of discounters. IP agreements should also be assessed carefully. Although certain restrictions are necessary to protect IP rights, some restrictions can raise concerns under competition law.

2. Global Trends

Europe

Competition legislation in each Member State will be derived from Articles 101 and 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ("TFEU") and will mirror its terms.

- Article 101 of the TFEU prohibits agreements, decisions or concerted practices which may affect trade between EU member states and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the EU; and

- Article 102 of the TFEU prohibits the abuse of a dominant market position within the EU.

Block exemption regulations have been issued by the European Commission (or in certain cases the European Council) for certain types of agreement, such as vertical agreements, technology transfer agreements and research and development agreements, which provide a safe harbour from Article 101 for agreements which fall within their parameters and which comply with their requirements. The Vertical Agreements Block Exemption is perhaps the most significant block exemption for supply agreements and the European Commission has issued guidance on its application and effect in the form of the Vertical Agreements Block Exemption Guidelines.

US

Key pieces of US legislation which regulate competition are:

- Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which declares every anti-competitive contract illegal;

- Section 2 of the Sherman Act, which provides that any person who shall monopolise or attempt to monopolise is guilty of a felony;

- Clayton Act, which prohibits price discrimination (section 3), exclusive dealing and tying arrangements (section 3) and mergers and acquisitions where the effect may substantially lessen competition (section 7); and

- Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, which prevents large buyers from exerting economic power to force suppliers to sell to them at prices lower than smaller, independent businesses.

The supply structure which is chosen may have an important impact on the extent to which competition law applies.

For example, in the case of distribution arrangements:

- Where a third party distributor of goods is chosen, competition law is likely to apply as it is an arrangement between two separate companies under which restrictions have been placed on the way in which products can be marketed.

- Where a producer sells or distributes its goods directly on the market as a result of being "vertically integrated", competition law is unlikely to apply as it usually applies to agreements between independent companies and not to agreements between companies that form part of the same undertaking.

Agency arrangements, under which an agent negotiates and sells products/services on the supplier's behalf, may avoid the application of competition law. Where a genuine agency agreement is in place (generally where the trader bears no significant financial risks in relation to his activities as agent), competition law does not apply to any restrictions imposed on the agent by the supplier. Agency agreements need to be reviewed in detail to check whether they fall within the definition of a genuine agency agreement under applicable national competition law.

Whatever the supply structure, competition law will always apply with respect to abuse of dominance issues, e.g. refusals to deal, predatory pricing, price discrimination, tying/bundling, exclusive dealing, discounting etc.

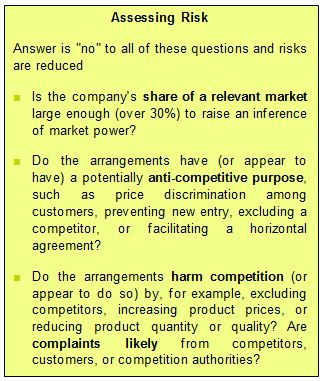

In identifying potential risk areas and practical steps to take it is helpful to categorise a range of activities which typically give rise to competition law concerns.

Resale price arrangements involve efforts by a manufacturer or supplier to control or influence the price that a distributor will charge its customers for the manufacturer's product. Minimum resale price agreements are usually unlawful, and many jurisdictions regard them as per se illegal. A few jurisdictions apply a rule of reason approach to the analysis of these agreements, finding them unlawful only if the anti-competitive effects outweigh the pro-competitive benefits of the arrangements.

Suggested resale price programmes, under which manufacturers provide suggested price lists to distributors or print suggested retail prices on packaging, may be lawful. However, these programmes may be risky and should be checked carefully by competition law counsel in advance.

Maximum resale price agreements generally do not pose competition law risk as they often protect consumers from higher prices and are therefore low risk. However, given the risks associated with resale price restraints any programme should, however be checked carefully by antitrust counsel.

- Territory and customer restrictions

Companies may seek to limit a distributor of the company’s goods or services to a particular sales territory or a particular type of customers. Such agreements between companies and their distributors typically do not violate the U.S. antitrust laws so long as they do not involve discussions or agreements among competitors or among the distributors. A more restrictive view may be taken of such agreements under the competition laws of the EU and other countries.

- Refusal to deal

As a general rule, most companies can decide unilaterally not to deal with a customer or supplier.

However, a unilateral refusal to deal may raise competition law concerns where the company has such a significant market share that its refusal to deal will have an adverse effect on competition by foreclosing its rivals' access to inputs or customers they need in order to compete.

- Predatory pricing

It may be unlawful for a dominant firm to sell products or services at prices below the company’s cost of producing those products in order to harm competitors.

- Price discrimination

Charging similarly-situated buyers different prices can infringe competition law under certain circumstances. This is particularly the case where the supplier can be regarded as dominant.

- Tying/Bundling

In some cases, competition law prohibits dominant firms from requiring a buyer to purchase product A (the “tied” product) in order to purchase product B (the “tying” product). On the other hand, merely offering a discount to customers who purchase several products or services together generally does not violate competition law, as long as the customers also have the realistic option of purchasing the products or services separately.

An exclusive dealing contract requires that a buyer deal exclusively with a particular seller. A requirements contract requires the buyer to purchase a certain quantity of products or services from a particular seller. These agreements may prevent the seller’s competitors from competing for the buyer’s business. The legality of these arrangements depends on a variety of factors and can only be determined on a case-by-case basis.

- Market share discounts, loyalty discounts, and “most favoured nation” provisions

Contracts may give a buyer a discount if the buyer promises to source a certain percentage of its purchases from a particular seller. Other contracts may guarantee a buyer that it is receiving at least as good a price as all other buyers. As with exclusive dealing and requirements contracts, these agreements may prevent certain companies from competing for the buyer’s or seller’s business. The legality of these arrangements depends on a variety of factors and can only be determined on a case-by-case basis.

- Information exchange

Suppliers should avoid facilitating anti-competitive information exchanges between their customers (so called "hub and spoke" or "A-B-C" arrangements).

If a supplier is found to have knowingly acted as a conduit for collusion between its customers, it may be treated as a participant in that cartel conduct, triggering potential liability for high fines and damages claims from third parties that suffered harm as a result of the collusion. This will be the case notwithstanding that the supplier is not active on the markets affected by the cartel.

4. Consequences of Getting it Wrong

There are significant risks both for businesses and individuals that do not comply with competition law. Businesses that breach the rules risk:

- Fines;

- Damages claims from customers or competitors who have suffered loss as a result of the anti-competitive behaviour;

- Being unable to enforce contracts; and

- Being ordered by competition authorities or courts to change business practices.

In addition, in some countries there are criminal penalties for individuals. Investigations by competition authorities also inevitably result in a significant diversion of management time and costs, damage to commercial relationships, adverse publicity for the business, and on-going suspicion.