Supply Chain: Issues & Analysis: Payment Terms

An analysis of the key considerations when setting payment terms in the supply chain.

1. Overview

The terms on which payment is to be made will be key to determining both the financial consequences and the financial risk associated with the contract.

Seen in the context of an entire supply chain, those terms become even more significant in both respects.

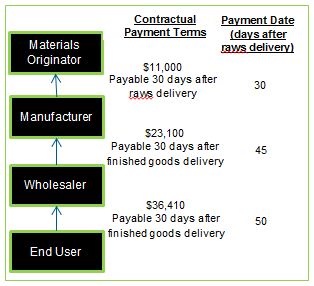

This is simply illustrated using a 4 link supply chain for goods in which each party carries its own direct cost of $10,000 and makes a 10% margin, manufacturing takes 15 days and a wholesaler's stockholding period is 5 days:

Commercial Impact: The difference in payment terms through the supply chain will create funding issues for Materials Originator, Manufacturer and Wholesaler.

Each will need to fund their own costs, and the amount they have to pay upstream in the chain, until they receive payment.

A shortening of the terms of any party upstream in the supply chain without an equivalent shortening in downstream terms will increase funding costs.

In this example, if the Materials Originator requires payment within 10 days of delivery then, unless the Manufacturer can secure a 20 day reduction in the terms on which it is paid, the Manufacturer will bear an additional funding cost.

This "chain effect" is highly relevant when examining the impact of legislative intervention with regards to payment terms.

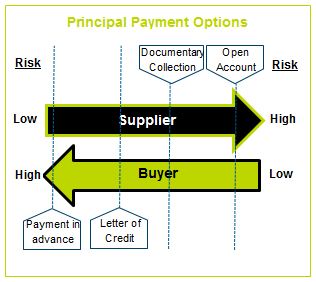

Risk Impact: The structure of payment terms will influence the risk that payments may not be made on time (or, possibly, at all).

The converse risk is that in certain circumstances amounts may be committed or paid buy contract performance may be delayed (or may never take place).

At one extreme, if the price is paid in advance the buyer will assume risk of non-performance. At the other, where payment is made after performance the supplier assumes a risk of not being paid.

There are four basic models:

- Payment in advance: payment must be made before the supplier performs its obligations;

- Letter of Credit: payment formally guaranteed by a bank;

- Documentary Collection: Payment executed through a bank on production on documents; and

- Open Accounts: Payment made following performance.

2. Global Regulatory Trends

Given the potential impact on suppliers of payment being delayed significantly, legislation has developed in a range of jurisdictions which seeks to protect suppliers.

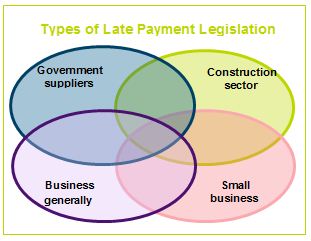

Regulation has generally looked at providing protection to four groups: (i) businesses who supply government; (ii) businesses involved in the construction sector; (iii) smaller businesses; and/or (iv) businesses generally.

However, the models are far from consistent and there is often a degree of overlap between various regimes.

Government Contractors: A large number of economies across European, North America and Australasia have rules which are intended to protect those supplying government in certain circumstances.

Typically the scope of these rules covers those relating contractors with a range of state related entities and agencies going beyond government departments themselves.

In many cases these rules are contained in legislation. For example, In many cases these rules are contained in legislation eg the Miller Act in the USA requires performance and payment bonds for federal construction projects.

In other cases the protection is embodied in a "Code of Practice" which is supported by declarations of intent by Ministers or other officials. For example, in the UK, the Office of Government Commerce requires as a matter of policy that all government sub-contractors are paid within 30 days.

The detail of rules protecting Government suppliers can vary significantly. In the EU various directives provide fairly sweeping protection for anyone supplying Government. By contrast, in parts of North America they are focused particularly on those involved in public sector construction projects.

Construction Sector: The protection of suppliers in the construction sector is also an important standalone theme in prompt payment legislation.

The case for special treatment in the construction sector is based on the scale and duration of construction projects and the extent to which the financial position of sub-contractors can be dictated by the terms of the head contract.

In parts of Europe, the concept of protecting construction contractors, even for wholly private sector projects, is well established. For example in the UK the Construction Act 1996 outlaws "pay when paid" provisions.

By contrast the approach in North America originated in the protection of Government contractors. However, Prompt Payment Acts covering wholly private sector construction projects have been significant since 2010 (for example the Prompt Payment Acts in Massachusetts and Vermont, among many, impose strict maximum timelines for review and action upon a contractor’s applications for payment and the making of payment).

Smaller businesses: The principle that smaller businesses require greater protection against delays in payment was reflected in the original legislation providing statutory protection in the EU, and detailed in the Small Business Act 2008.

Elsewhere protection of this nature is generally confined to codes of practice, such as the UK's Prompt Payment Code, which government agencies and larger companies may sign up to voluntarily. Such codes have been criticised for being ineffective due to their voluntary nature – in the UK, small and medium enterprises ("SMEs") are collectively owed late payments of some £30.2bn. This is because SMEs are commonly unwilling to enforce their statutory remedies and protections against late-paying customers, for fear of damaging relationships with customers, clients and contractors.

Business generally: The European Rules go significantly further than those in operation anywhere else in the world in providing protection for suppliers under any contract.

The European Late Payments Directive affects any supply contract involving one or more parties based in the EU. Member states were required to implement to the directive by March 2013, and it obliges public authorities to pay invoices for goods and services within 30 days. This is extendable to 60 days only in exceptional circumstances. In contrast, purchasers that are businesses have discretion to extend the payment period to 60 days, but both parties to the agreement must agree to an extension beyond 60 days, which will only be valid if not "grossly unfair" to the supplier. Any defaulting purchasers are required to pay interest at 8% over the national reference rate plus the supplier's compensation costs for recovering the debt.

As noted above, however, SMEs are disproportionately affected by late payments, even with such legislative protection. The EC is currently working to increase awareness amongst European stakeholders, both business and public authorities, on the rights and obligations conferred by the directive.

3. Impact of Regulation on the Supply Chain

In most cases regulation primarily applies to bilateral contracts. To a greater or lesser extent regulation will do one or more of the following:

- Set maximum payment periods;

- Provide for mandatory interest; and/or

- Outlaw specific provisions (e.g. "pay when paid")

Much regulation also includes complex "choice of law" provisions which are intended to prevent parties artificially avoiding the impact of the rules by the selection of the governing law of their contract.

Differences in the impact of payment terms regulation will indirectly affect many supply chain relationships beyond directly regulated contracts.

In particular, if part of the supply chain flows through a regulated jurisdiction or constitutes a regulated relationship, the terms imposed by regulation are likely to have a ripple effect on the remainder of the chain.

For example:

- if payments made to a supply chain participant downstream are unregulated payment then terms may well extend. This may result in your customers paying you slowly.

- if, by contrast, payments which are required to be made upstream are regulated then those payment terms will contract. This will result in you being under pressure to pay your suppliers quickly.

4. Termination for Non-Payment

Unless the contract is explicit, in many jurisdictions it will not be straightforward to terminate even where the buyer is not paying.

For example, under English law unless the contract provides that payment is "of the essence" or otherwise provides the supplier with express rights of termination on non-payment, the supplier will need to serve a period of notice giving the buyer a further opportunity to pay before the supplier is entitled to terminate. This can be particularly difficult for a supplier in a continuing relationship as it may be obliged to continue to supply the product even in a scenario where it is not being paid. Alternatively, depending on the circumstances, persistent non-payment can amount to a repudiatory breach of contract if the consequences are serious enough. In such a case the innocent supplier may be entitled to terminate with immediate effect and can apply to the courts for damages.

In contrast, in the Civil Law jurisdiction of France, without a clause giving automatic rights of termination to an aggrieved party (a "clause résolutoire") being written into the contract, the agreement can only be terminated by order of the court. Such clauses are strictly interpreted, and it must be specifically stated that the clause constitutes an exception to the French Civil Code rule of judicial termination of contract. Merely stating that late payment or failure to pay will give the supplier the option to terminate the contract is insufficient. The supplier must also give sufficient notice, irrespective of the contractual notice period. However, if the buyer defaults on payment or is late making payments, the seller is not obliged to deliver goods under contract.

Conversely, under the German Civil Code, the seller is entitled to withdraw from the contract and terminate it if the buyer defaults on payment, provided it gave the buyer an adequate period of notice in which to pay (with what is "adequate" depending on the length of the relationship).

This right of termination for non-payment, subject to adequate notice, is also prevalent in Japan, where a contract is generally enforceable in accordance with its written terms.

Parties contracting under Chinese law can include a negotiated termination clause, and/or be permitted to terminate on breach of a "main obligation" of the contract which is not rectified within a reasonable time. There is no statutory requirement for notice, however. Note that termination clauses are often among the most heavily negotiated. This is because it is a common perception among Chinese parties that a foreign counterparty may seek to use a termination right unconscionably, either to avoid its contractual obligations or to end a contractual relationship that still has value to the Chinese party ahead of time.

In the USA, the Uniform Commercial Code (as implemented in each state) generally governs supply contracts. A seller is entitled to "cancel" (terminate and retain any rights for breach) the contract if the buyer fails to make a payment when due. The retained right for breach will include the right to charge interest on late payments (as long as the amount charged is not excessive, punitive, or in violation of laws with regard to usury). Note that some states require a minimum notice period for termination.

Back to top

5. Retention of Title Clauses

Such clauses provide that the seller of goods retains title, or ownership, over the goods until it receives full payment. This therefore gives the seller priority over all creditors of the buyer if the buyer fails to pay. for example due to an insolvency-related event , and entitles the seller to recover the goods to minimise its loss. An enhanced "all monies" clause can reserve title until the seller has paid for not only the goods under the contract in question, but for any other goods supplied by the seller.

However, in the UK, if the company is in financial difficulties, it may be necessary to apply to court for permission to repossess the goods pursuant to a retention of title clause. The obstacle created by creditors of the buyer is also an issue when considering retaining title in the US. Furthermore, the clause may be ineffective in the UK if its operation is inconsistent with the overall trading relationship between parties.

In France any retention of title clause must be in writing and this is contrary to the general rule that oral commercial contracts can be valid. The clause must be clear and intelligible enough so as to establish that the buyer had full knowledge of it before contracting. If the buyer is in insolvency, though, the clause is always enforceable against creditors unless agreed otherwise.

In Germany, the retention of title is enshrined in the Civil Code, which provides that transfer of title to the buyer only takes place when the purchase price is paid in full. In general there is no need for the retention of title clause to be written, unless the Civil Code requires the title to be in a specific form.

In contrast in the US, as retention or reservation of title clause is only limited to a "reservation of a security interest". In practice, this means that a seller cannot use a retention of title clause as the basis for repossessing goods. Any reclamation of goods is subject to the federal Bankruptcy Code. Ultimately, a seller may not be able to take priority over a creditor with a prior perfected security interest. Therefore it is common for sellers of goods to create and enforce security interests in compliance with the Uniform Commercial Code rather than relying on retention of title clauses.

Back to top