Go Global: Issues and Analysis: Creating a Contract

1. Overview

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement which gives rise to rights and obligations for the parties. The fundamental purpose of a contract is to set out clearly what each party is supposed to do and the consequences if they don't do it. It is the instruction manual for the trading relationship between the parties and should allow them to define and know the parameters and rules of their trading relationship.

There are several "must haves" that should be expressly dealt with in every contract:

- who is doing what for whom and when? and

- the consequences if they don’t comply with their obligations!

In addition there are some points that the contact should or may need to deal with: where, how and why the contract is to be performed?

Given the irrefutable importance of a legally binding and enforceable contract to a successful trading relationship, a perennial question which is common to contracting parties in every jurisdiction is:

Have I got a legally binding contract?

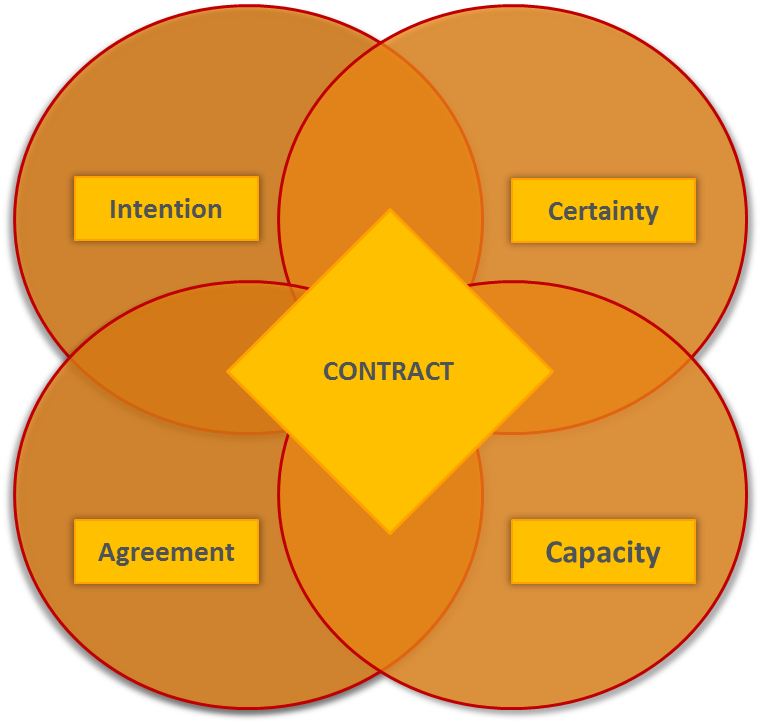

Although the essential elements of a valid/enforceable contract vary between different jurisdictions, the most basic common legal concept is the need for an agreement and most jurisdictions try to identify the point at which an agreement that has legal consequences has been reached.

The key common elements for a legally binding contract are:

- Agreement of terms;

- Certainty of terms;

- Legal capacity to enter into the contract; and

- Intention to create a legally binding relationship.

Agreement

Agreement is often expressed in terms of an offer to enter into a contract being made on terms that are accepted in full. In this context, a distinction is often drawn between an "offer" that is capable of being accepted in a way which forms a legally binding contract, and "an invitation to treat" which signifies only a start to negotiations and is not capable of becoming legally binding and so forming a contract. Although many jurisdictions make this basic distinction, the precise application may vary.

Certainty

A fundamental principle of contracting, which is recognised the world over, is that the terms of the contract must be sufficiently clear and complete to be enforceable. The degree of uncertainty that will be tolerated before the contract becomes unenforceable differs from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, with the courts in different jurisdictions displaying varying levels of willingness to interpret and even re-write a term that is not transparent in its effect. However, the common denominator is that the terms of the contract are sufficiently certain to enforce if they provide a basis for determining the existence of a breach of the terms and for giving an appropriate remedy. The need for certainty does not just apply to the individual terms of the contract and the general rule is that an agreement that is missing one or more essential terms is unenforceable.

Civil code contracting v common law contracting: The requirement for the contract terms to be complete (i.e. all the essential terms have been agreed by the parties) is a more significant potential pitfall for common law legal systems than civil code legal systems. This is because civil code legal systems are based upon a collection of codified laws set out in statutes which, generally, set out all the essential terms of the contracts which fall within their scope and these statutory terms automatically form part of the contract in the absence of the express agreement of the contracting parties to modify or disapply the terms.

Therefore, in the civil code contracting process the contracting parties do not have to negotiate or agree their contract in as much detail as common law systems, provided that they are prepared to accept application, content and effect of the applicable jurisdiction's statutory standard contract terms. In comparison, common law legal systems give great precedential weight to case law or precedent and are developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through statute. In the common law contracting process the contracting parties need to expressly agree all the essential terms of the contract as there are relatively few terms implied into contracts, either by the common law or statute. Also the circumstances in which the court will consider implying an essential term into a contract to render it complete and enforceable are very limited (usually requiring that the missing clause had been in the contemplation of the parties during the contracting process but inadvertently omitted when the contract was concluded). This means that there is a much greater risk of a contract being deemed incomplete and therefore unenforceable under the common law contracting process than the civil code contracting process. For more information on implied terms see Go Global: Implied Terms.

Intention to create a legally binding relationship: Courts will usually look for an intention of each of the contracting parties to create legal relations and the basic rule of thumb is that where there is no intention, there is no contract. However, there are marked differences between jurisdictions as to what conduct will and will not suffice to demonstrate an intention to be legally bound and this diversity can often manifest itself in the response of an individual jurisdiction to the question: “At what point in the negotiation of a contract does the contract become legally binding?”

In many jurisdictions there is a rebuttable presumption that, in commercial circumstances, the parties intend their agreement to be legally binding and an objective test is used to decide if the parties have the requisite intention, i.e. would reasonable people regard the agreement as legally binding?

Consideration: In addition to capacity, agreement, certainty and intent, most jurisdictions require some form of consideration (e.g. payment of some form) for a contract to be legally binding, although in some circumstances a bare promise that is not supported by consideration can be legally binding. The definition of what constitutes “good consideration” varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction but can include money or money’s worth or any other value given at the counterparty’s request including any action, inaction, or a promise.

Pre-Contractual Discussions

Can discussions undertaken before formal contracts are entered into ever be binding or give rise to liability?

Generally, pre-contract discussions are not considered to be legally binding, in the sense that the contractual terms that are being discussed or negotiated do not become an enforceable contract unless and until the essential elements for the creation of a legally binding agreement required by the applicable governing law are present (e.g. agreement, intention to create a legally binding contract, legal capacity, certainty and completeness of terms, consideration etc). In many jurisdictions both (i) the intention to conclude a legally binding contract and the terms of that contract can be deduced from both the conduct of the parties in oral discussions and (ii) the content of any pre-contractual documentation which has been shared by the parties.

However the discussion can create liabilities for the entities carrying out the discussions that are separate from any liability that arises from the contract, if any, which is concluded as a result of the discussions. For example, many jurisdictions have laws that protect confidential information that is disclosed as part of the discussions, placing an obligation upon the recipient of confidential information to preserve its confidential nature and to not make commercial use of the information without the permission of the owner of the confidential information. Some jurisdictions, for example many civil code legal systems, impose a duty to negotiate in good faith and some, such as Spain, even impose a duty of loyalty on negotiating entities. Other jurisdictions, such as the UK, do not impose a general duty of good faith but do give remedies where a party has entered into a contract as a result of the misrepresentation of another party.

In many jurisdictions the participants in the discussions are free to stop and walk away from the discussions at any point without liability, on the basis that they cannot be forced to enter into a contract. However there are some jurisdictions, such as Germany and Spain, which will compensate a participant in pre-contract discussions who has been led to believe by the other participant that, essentially, the “deal is done” and that all that remains to be done is the signing of the contract if the other participant refuses, without good reason, to enter into the contract.

Pre-contract documents such as heads of terms, letters of intent and memorandum of understanding which outline the general terms of the proposed contract but do not set out the actual terms do not tend to be legally binding unless the parties agree that any or all of their terms are intended to be legally binding and they satisfy the requirements for a legally binding contract. The terms which are commonly expressed to be legally binding deal with confidentiality, costs and expenses, governing law and jurisdiction and the exclusivity or otherwise of the negotiations.

Can pre-contractual discussions or agreements commit particpants in negotiations to negotiate on an exclusive basis?

A common concern for participants in a negotiation is that merely entering into the discussions will commit them to negotiate with the other parties on an exclusive basis, essentially preventing them from running parallel discussions with other potential contracting parties, for example as part of a tendering process. Generally, the answer is no, unless the partcipants have expressly agreed to negotiate exclusively and such agreement satisfies all the requirements for a legally binding agreement.

There may be competition concerns which arise from an agreement to negotiate exclusively and such agreements must be compliant with the applicable competition law to be enforceable.

2. Contracting Formalities

Are there any specific requirements before commitments given can become contractually binding?

Many jurisdictions allow contracts to be entered into orally, in writing or a mixture of both and many do not have specific formalities that must be observed when concluding the contract.

However, many jurisdictions require certain contracts to be in writing (for example mortgages, transfers of land, contracts which exceed a certain value and/or duration, assignments (particularly of intellectual property rights), gift or contracts entered into by a specific type of entity) or notarised or entered into as a written deed. In some jurisdictions, such as China, some companies are established as special purpose vehicles that are authorised only to engage in specific types of commercial activities and may only enter into contracts which relate to the authorised activity. Furthermore in China there is a distinction made between contracts that require governmental authorisation and which will be void without such authorisation and other contracts which are only required to be registered and which will not be rendered void for lack of registration.

What are the main formalities that need to be observed for execution of a contract?

Individuals

A fundamental requirement is that individuals must have the requisite mental and legal capacity to enter into the contract and the two common elements required by most jurisdictions is that the individual must be an adult or at least over a certain age threshold and must not be mentally incapacitated.

Corporates (e.g. limited companies)

Each jurisdiction has its own specific requirements for the way in which corporates execute contracts, which may be subject to variables such as the nature and significance (commercially, legally and financially) of the contract. However a common requirement is that the person or entity that executes the contract on behalf of the corporate must be authorised to do so in the manner required by the jurisdiction.

Other forms of business entity (e.g. charities, parterships etc.)

As with corporates, each jurisdiction has its own specific requirements for the way in which non-corporate business entities, such as partnerships, execute contracts and the method required usually depends on the nature of the entity and its legal identity.