Supply Chain: Issues & Analysis: People Considerations

1. Overview

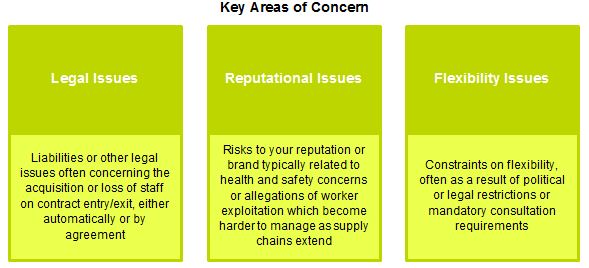

People issues can be critical when thinking about the supply chain and related contractual provisions.

The appropriate way to address these issues depends on the nature of the concern.

There are limits to what can be achieved in a contract. Some issues, notably those in the legal category relating to the acquisition or loss of staff, will be susceptible to a contractual solution. By contrast, while contractual terms can be used to minimise the risk of reputational damage, full due diligence on the counter party may be a better approach to managing risk in this respect. On-going collaboration between suppliers and end users to support acceptable workplace standards may be another solution.

Contractual provisions will also need to reflect political and legal constraints in different regions. This is particularly the case in jurisdictions where employment protection laws offer enhanced consultation, or in some cases co-determination, rights.

Employment protection laws clearly have an impact on the speed at which it may be possible to introduce changes to different parts of the supply chain and the flexibility that different counterparties may be willing or able to accept in this regard.

People transfers

A key people issue that arises in connection with supply chain contracts is whether the contract will give rise to a business transfer so that employment protection rules transferring staff automatically from one party to another by operation of law will be engaged.

Such automatic transfer principles are standard across the European Union and common in many South American countries. They are less common in North America and the Asia Pacific region. For example, there is no automatic transfer principle in either India or China, although staff may be entitled to a termination payment if their employment is terminated in connection with a business transfer. The position is also mixed in Africa, although South Africa does have an automatic transfer principle.

From a European perspective, a transfer of an undertaking usually involves a transfer of tangible or intangible assets, including employees, from one party to another. Outsourcing arrangements can also amount to business transfers:

- In some jurisdictions, such as the UK, there is a presumption that an outsourcing will give rise to the automatic transfer principle; and

- In most other jurisdictions whether or not an outsourcing amounts to a transfer will be judged on normal principles.

When considering an outsourcing, consideration normally has to be given to whether the arrangement will trigger an automatic transfer. The issues to which automatic transfers give rise that may need to be addressed in a supply contract are outlined below.

Reputational issues

Over recent years there has been an increasing focus on corporate social responsibility (CSR).

One strand of CSR aims to ensure that the working conditions of employees reflect international minimum standards. While there are many factors that influence an organisation's decision to engage with CSR, one relevant factor may be a desire to avoid being associated with a supplier's poor working conditions or health and safety violations, such as the 2013 Bangladesh factory collapse.

The degree of risk associated with CSR issues will obviously depend both on the type of work that is being carried out and the location of the work. Embedding CSR as a factor in the tender process and conducting adequate due diligence on the counter party are ways of assessing risk. As supply chains lengthen, the risks potentially increase, with the ultimate client having less control over CSR compliance in companies with which it does not have a direct contractual relationship.

Another point to bear in mind when considering CSR issues is the increasing emphasis on voluntary and in some cases mandatory disclosure requirements.

From 30 September 2013 quoted companies have had to prepare strategic reports that include information about social, community and human rights issues (amongst other things).

Proposal for an EU directive would require large companies in European member states to include a statement in their annual reports detailing information about their policies on social and employee matters and respect for human rights.

Requires listed companies to publish CSR information in annual reports.

In addition to requirements in Europe, a number of countries in the Asia Pacific region also require listed companies to publish CSR information in their annual reports or adopt a "comply or explain" approach requiring companies to report on CSR issues or explain why they have failed to do so. It is obviously important to ensure that the approach adopted for supply chain contracts is consistent with any public CSR disclosures that are made, whether on a mandatory or voluntary basis.

Flexibility issues

Businesses need to consider whether there are any labour market restrictions on flexibility in any of the jurisdictions in which they are planning to base elements of the supply chain. Some countries,such as India and Brazil, impose local minimum content requirements in some industries. Consideration obviously needs to be given to whether there is sufficient local expertise to meet those requirements and, if not, how that issue can be dealt with.

In contrast, in other jurisdictions, notably continental Europe, there may be political, industrial and/or legal barriers to exit rather than entry. In France there is often significant political pressure not to shut plants or transfer work to lower cost jurisdictions, often accompanied by industrial disruption.

Employment consultation rights may mean that it takes longer to take a business decision (for example to shift a production location) in Europe than is the case elsewhere. For example, if an employer in the Netherlands is proposing collective dismissals, he must seek the advice of the works council before any decision is taken and at a time when the works council can have a significant impact on the decision that is taken.

That process can take up to three months, during which time the collective dismissals cannot proceed. In other countries, including Colombia and Indonesia, as well as some European countries, authorisation from labour authorities is required before dismissals can go ahead.

If dealing with a multi-national employer in Europe which has a European Works Council, business decisions that have an impact in more than one country (such as a decision to move a plant from one country to another) will trigger additional consultation obligations. Depending on where the European Works Council is set up, decisions that are taken without proper consultation can be rendered void until the required consultation has taken place. This level of employment protection obviously has the potential to reduce flexibility in the supply chain.

Legal issues

As far as legal considerations are concerned, if the contract being entered into amounts to a legally recognised business transfer, the parties will have to think about a wide variety of issues, including:

- Whether staff will transfer from one party to another (or from an existing to a new supplier) automatically as a matter of law;

- If so, whether the transferee needs such staff, and if not what arrangements will be put in place to deal with any resulting dismissals (effectively, who will bear any redundancy cost, where a switch of supplier is contemplated the provisions of the existing arrangements need to be reviewed to assess where any contractual liability for redundancies may fall);

- On a first generation outsourcing in particular, is contractual protection for staff terms and conditions required that goes beyond minimum legal protections in order to minimise the risk of industrial unrest/ achieve staff buy-in?

- If there are employees who are key to the provision of the contract, what contractual provisions are needed to ensure they remain assigned to the contract and are not re-allocated to other parts of the business, and does the client need to be involved in the selection of a replacement if a key employee leaves?

Slightly different considerations come into play if there is no automatic transfer of staff:

- If staff do not transfer automatically, what arrangements need to be put in place to achieve a transfer of necessary or key staff?

- What provisions are needed to preserve the position of each party with regard to employees on exit (in other words, who should bear the risk of any dismissals arising from a termination of the supply contract if there is no automatic transfer of staff)?

- If staff are not expected to transfer on exit, are anti-poaching clauses needed to protect the stability of either party's workforce for a period when the contract ends?

Depending on the nature of the contract, the risks of acquiring or losing staff may be dealt with through contractual commitments that one party will bear all or a proportion of the particular costs associated with redundancies on entry/ exit. In the absence of such protection the risks are typically priced in to the contract.

Reputational issues

From a contractual perspective, provisions can be included in the contract to try and minimise the risk of reputational damage from people issues in the supply chain. Issues to think about include:

- Obtaining a commitment to observe CSR standards;

- Confirming that the other party has a CSR policy and conducts its business in accordance with those standards;

- Requiring the counter party to enter into similar CSR obligations with its own sub-contractors; and

- Monitoring compliance with CSR standards by the other party (through site visits or other audit mechanisms or tools).

Alongside contractual requirements of this nature, collaboration with suppliers, and in some cases with competitors (if permitted by law), to identify and minimise areas of particular concern is increasingly recognised as a way of reducing CSR risks in the supply chain.

Constraints on flexibility

Some (although obviously not all) of the practical constraints on flexibility can be addressed contractually.

From a supplier's perspective, it may be necessary to negotiate a sufficiently long notice period that will allow consultation obligations to be complied with in the event of termination where staff will not transfer to a new supplier. As indicated above, the costs of any redundancies on termination of the contract may also need either to be priced in to or allocated in the contract itself.